Lessons from Sobukwe, Africa’s Son of the Soil and Prison No. 1 on Robben Island

Howard on Africa In-Brief

A publication of the Center for African Studies, Howard University

Lessons from Sobukwe, Africa’s Son of the Soil and Prison No. 1 on Robben Island

by DaQuan Lawrence

July 16, 2025

In an era where rhetoric, media and political messaging seem to revolve around buzzwords like ‘authoritarianism,’ and ‘fascism,’ examinations of how human rights defenders and social justice institutions can address American hegemony and the white supremacist establishment are necessary.

The Republic of South Africa and Robert Sobukwe, the renowned imprisoned anti-apartheid activist, offer insights for enduring and transforming political despotism. The nation was once led by a separatist government that persecuted, imprisoned, tortured and killed political dissidents for demanding justice and human rights, including Sobukwe, who is often overlooked in contemporary political discourse yet continues to inspire generations.

South Africa’s rich history and engagement in revolutionary struggle from political oppression make the nation a strong case study for political and civic engagement in the modern global political economy, and a regime mired by tyrannical governments.

Between implementing unprecedented tariffs against international economies to “diminish the U.S. trade deficits,” threatening to withdraw support for North American Trade Organization (NATO) and its European allies, and altering diplomatic ties and trade relations with nations such as Canada and Mexico, the Trump administration is quickly seeking to transform America’s relationships with foreign nations.

There are historical precedents, both domestic and foreign, that provide guidance for addressing contemporary racialism and political subversion whether one is politically an opponent or proponent of President Donald Trump and state repression. Despite the political preferences of voters and elected officials, people dedicated to human rights view them as nonpartisan issues and commemorate the legacies of those who fought for human liberties.

Much of the international community is aware of Nelson Mandela’s role in South Africa’s road to freedom, yet many people are less familiar with his contemporary, Sobukwe and the invaluable role he had during South Africa’s struggle against the repressive and racist apartheid South African government.

“Sobukwe was more of a fighter than Mandela when it came to liberating South Africa,” Tumi Hlatshwayo, founder/chairperson of Voice Into Dance Art (VIDA), a nonprofit organization that provides developmental opportunities for youth and talent throughout the Gauteng province.

VIDA operates in Wattville and Benoni, South Africa, and Hlatshwayo, who grew up in Johannesburg during the 1970s and witnessed the impact of Sobukwe’s efforts, explained the distinctions between Sobukwe and Mandela’s approaches to resisting the fascist, apartheid regime of 20th century South Africa.

“Sobukwe was very much loved because he wanted Black South Africans to have land, while Mandela wanted to share the fruit of Black South Africans with white monopolists. I believe that's why Sobukwe decided to part ways with the ANC,” Hlatshwayo said.

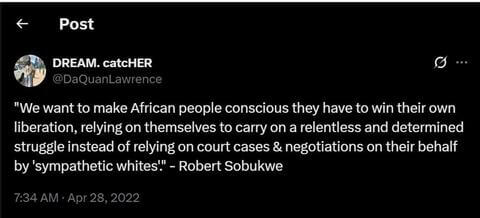

Pan Africanists around the globe find inspiration from Sobukwe’s involvement during South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement.

Netfa Freeman, an organizer for Pan African Community Action (PACA) and the Black Alliance for Peace, and co-producer/host for the radio show and podcast Voices With Vision on WPFW 89.3 FM, believes that political repression needs to be addressed in modern society.

“The international analysis is clear that we have an imperialist global system and require an anti-capitalist movement. Sobukwe and the PAC believed there was a relationship between capitalism, white supremacy and the usurpation of land in South Africa,” Freeman said.

“The U.S. has always tried to maintain a resemblance or facade of benevolence, especially with South Africa, where they supported the apartheid regime yet condemned them publicly at the same time,” Freeman said.

According to the Democracy Toolkit, a project of Howard University's Center for Journalism and Democracy, “authoritarianism, populism and fascism are distinct yet interrelated facets of democratic backsliding, [where] democracies incrementally deteriorate into less open and more repressive regimes.” The project advises journalists to understand how such terms are related as media professionals “hold power to account” and safeguard democratic institutions and discourse.

South African-U.S. relations were strained and likened to a fragile ‘tightrope’ prior to the current administration, yet Ebrahim Rasool, South Africa’s Ambassador to the U.S. was declared persona non grata on March 14, dismissed from the nation. President Trump also engaged in an awkward exchange during a bilateral meeting with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa after being misconstrued about allegations of white genocide in the country.

The “Rainbow Nation” is well known for its mineral wealth and cultural influence – as indicated by the world’s quick adoption of the gold and diamond rushes of the 19th and 20th centuries – and more recently amapiano music during the 21st century.

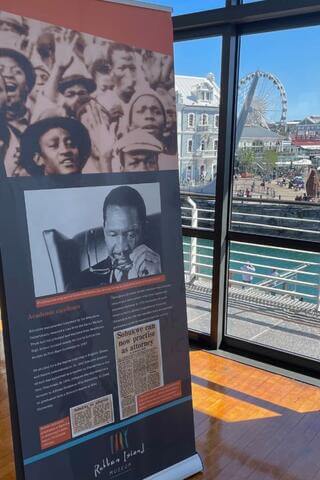

South African anti-apartheid activist, politician, educator and lawyer Sobukwe was one of many South African freedom fighters. His unusual level of influence, response to state authoritarianism and imprisonment - which led to a period where his teachings were banned or absent from historical and modern accounts of political discourse - set him apart.

According to Luvuyo M. Dondolo, professor of history at the University of South Africa, and author of “One Race: Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe,” despite Sobukwe’s contributions to the South African freedom struggle, his ideas remain “largely unknown” and [many] audio recordings of his speeches were hidden or destroyed. The African Film Festival of New York noted that Sobukwe was “once one of the most watched, recorded and popular political prisoners in the world.”

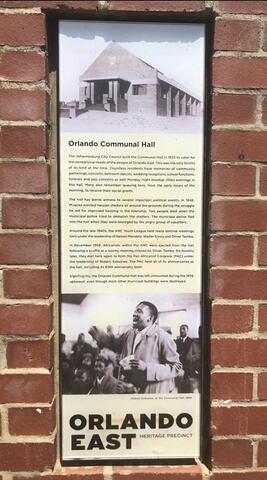

Between 1948 and 1958, Sobukwe was a leader within the ranks of the African National Congress (ANC) serving as ANC Youth League National Secretary and as secretary of the Standerton branch, before departing to create the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC).

At the inaugural convention of the PAC in 1959, Sobukwe declared his vision for the future of the country, stating “economically we stand for a planned economy and the most equitable distribution of wealth…and the slogan of ‘equal opportunities’ is meaningless if it does not take equality of income as the springboard from which all will take off.”

“When discussing history and Robert Sobukwe’s actions, it is important to contemplate historical events and modern South African politics because speaking hastily implies ignorance of true history,” Terence Sikweza, a doctoral student in Tshwane, South Africa, said.

“Sobukwe is remembered in the African National Congress circles, but globally his actions are camouflaged and clouded by what Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko did. Sobukwe is the man,” Sikweza, who believes in pan africanist ideals, said.

At the end of the fall 2024 semester the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP), PACA, the Black Alliance for Peace, Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and Africa World Now Project cosponsored a viewing and discussion of the 2011 film “Sobukwe: A Great Soul” at Sankofa Video Books & Café. WPFW 89.3 FM and Positive Productions Inc. were also partners for the convening.

After the documentary, WPFW 89.3 FM’s Katea Stitt held a discussion with Nancy Wright of the A-APRP and filmmaker Mickey Madoda Dube, an international film and TV director, producer and Fulbright Scholar at the USC's School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles.

Freeman attended the viewing and said he was surprised by the high regard people had for Sobukwe, despite Mandela's widespread recognition. He highlighted the differences between the ANC and PAC, and admired how the film emphasized why the PAC was established,and remains necessary in contemporary South Africa.

“I wish the film had drawn out the distinctions between the PAC and the ANC, or if you want to say Sobukwe and Mandela, in terms of the implications of the PAC’s Africanism, and its anti-capitalist, pro-socialist stance,” Freeman said.

“What made the PAC so relevant was the understanding and acknowledgement that the Freedom Charter didn't deal with the land question,” he continued..

According to the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, South Africa, the ‘land question’ is how to address historical colonial land displacement and centuries of racial land misappropriation within the nation. The Freedom Charter is a product of the Congress of the People, which attempted to create an alliance of anti-apartheid groups in the 1950s.

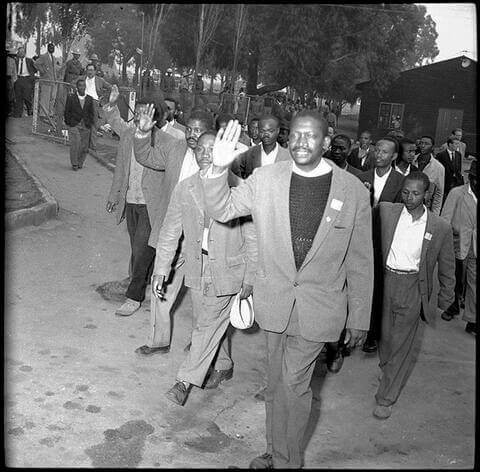

The film showcased the Sharpeville Massacre on March 21, 1960 where Sobukwe led thousands of citizens to a local precinct to voluntarily request their arrest to protest against the discriminatory ID-pass laws, and police fired on unarmed peaceful protesters shooting many of them in the back.

According to Bailiey’s African History Archive, the PAC wanted to make the laws unworkable as a first step in a long campaign to achieve ‘freedom and independence’ for Africans by 1963.

Kubheka is an elder in the Sunnyside, Tshwane community, who is originally from the Johannesburg metropolitan area. He discussed the anti-pass protest and said Sobukwe’s actions influenced South African people’s views about the political and economic landscape, and impacted people globally.

“Black people were required to carry IDs that we called ‘dog passes’ which allowed us to enter a white residential or commissioned area, which were exclusively reserved for whites. This is why the United Nations (UN) commemorates March 21st, as it serves to condemn the police brutality that killed between 67-69 people during a peaceful protest against discriminatory laws,” Kubheka said.

Kubheka mentioned that the global community should recognize Sobukwe because he was one of the first anti-apartheid activists to conscientize the international community about the apartheid government, fostered unity amongst African countries, and informed African nations about Cold War era geopolitics.

After the Sharpeville events, Sobukwe’s arrest and celebrated status among Black South Africans led to a special session of the UN, where he was declared “Prisoner No. 1 on Robben Island.”

Initially sentenced in 1960 to three years for inciting protests, on May 1, 1963, when many anticipated his release, the court announced that Sobukwe would remain detained “under the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950, as amended by the General Law Amendment Bill” which allowed the court to extend the term of an inmate.

The apartheid government passed the General Law Amendment Act of 1963, a special statute now called “the Sobukwe Clause,” to keep him and his ideas separate from prisoners in South Africa and the rest of the world.

Sobukwe was then moved to Robben Island, where he remained for six years. While on Robben Island, Sobukwe was restricted to solitary confinement, his living quarters were separate from the main prison and he did not interact with any other prisoners.

The ‘Sobukwe Clause’ was never used to detain other South African citizens, and each year it was due to expire on June 30, the government renewed it.

The U.S. and South Africa have a shared history of deeply rooted internal racial issues, tensions and divisions as both nations are internationally known for uniquely repressing their ethnic populations and political dissidents.

Responses to the Trump administration’s policies have included criticism, and accusations of racism and discrimination as reported by The Guardian and The New York Times, as well as domestic and international comparisons between democracy and authoritarianism in Western nations according to the European Center for Populism Studies.

In late 2024, CBS reported that John Kelly, Trump’s former chief of staff, said that Trump prefers a dictatorial style of leadership. Researchers at UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute have also identified the increasing trend of ‘authoritarian populism’ within politics, citing Trump’s political similarities with European leaders such as Italy’s Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, and Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán.

During the apartheid regime Sobukwe was clear that Western democratic societies were embedded with racial disenfranchisement and economic underdevelopment, yet he worked to address systemic issues and espoused a vision of hope.

“History overlooks that Sobukwe played a crucial role in fighting to dismantle the highly discriminatory apartheid pass laws, which forced Black South Africans to settle in townships that had no jobs, trade or land to sustain our families,” Kubheka said.

Decades later, the global community still has much to learn from Sobukwe's efforts against state repression in 20th century South Africa, as they can help current and future generations of human rights defenders battle racial and economic injustice and navigate the modern road to freedom.

DaQuan Lawrence is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of African Studies at Howard University.

Acknowledgements:

Howard on Africa in Brief is published by the Center for African Studies at Howard University. Contributors include prominent scholars, policy makers, Howard faculty, alumni and graduate students. Our papers provide open access to research and make a global contribution to understanding Africa-related issues. The views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s).