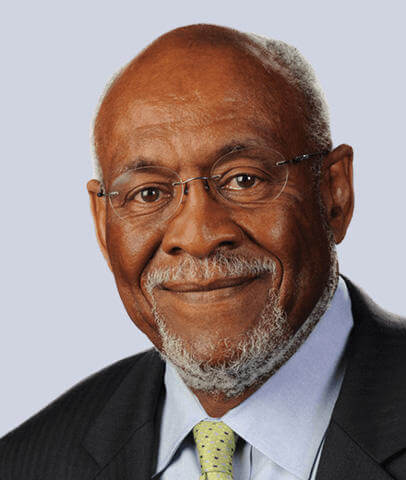

Comments by Amb. Johnnie Carson at Howard University's 2021 Symposium: Re-Shaping US-Africa Policy and the Role of HBCUs

Howard on Africa In-Brief

A publication of the Center for African Studies, Howard University

Comments by Amb. Johnnie Carson at Howard University's 2021 Symposium: Re-Shaping US-Africa Policy and the Role of HBCUs

Transcribed by Muhammad Fraser-Rahim, Ph.D.

March 2021

Ambassador Johnnie Carson, U.S. Institute of Peace and Former Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of African Affairs spoke at the Symposium: Re-Shaping US-Africa Policy and the Role of HBCUs on February 19, 2021.

Key Takeaways

• Howard University remains an important and critical player amongst HBCU’s and overall US-Africa relations;

• Encouraged by the changes, and recognizing the continent’s growing importance, successive Democratic and Republican Administrations embraced Africa.

• The Bush and Obama administration brought about formalized partnerships between Africa and the U.S. including humanitarian, security and economic cooperation;

• The last four years under the Trump Administration marked a low point in U.S. relations with Africa – reversing the steady improvement which followed the end of the Cold War;

• President Biden’s victory is good news for Africa;

• This is the moment to recognize Africa's intrinsic importance with regards to international community, its rising middle class and youth bulge and entrepreneurism/economic opportunity.

Comments from the Ambassador

Thank you for that very kind introduction. And thank you again for inviting me to participate in today’s conference. Howard has a very special and important place among HBCU’s and also in the history of U.S.-Africa relations. Howard has trained and educated thousands of African students -- many of whom have made enormous contributions to their countries and some of whom have become ambassadors, cabinet members and presidents. Howard has also produced a large number of Black American diplomats and international civil servants from among its students and its illustrious faculty. Today’s program is a continuation of Howard’s active engagement in helping to shape U.S. views, attitudes and policy toward Africa.

I was asked to say something this morning about U.S. policy in Africa in the post “Cold War” era – which effectively ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

I think it is important that as we look ahead to a new era in U.S.-Africa relations that we need to look back to learn from the past in order to avoid repeating old policy mistakes.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991 marked a significant inflection point in U.S. policy toward Africa.

Prior to the downfall of the Soviet Union, American political and diplomatic engagement in Africa was heavily influenced by the intense and sometimes confrontational relationship between Washington and Moscow. Although there were some bright spots in Washington’s engagement with Africa, (including the assignment of hundreds of Peace Corps Volunteers and the provision of millions of dollars of food aid and foreign assistance), Africa was largely a small piece on the chess board in East-West relations.

Cold issues were dominant and democracy, human rights and good governance were not at the forefront of our policy dialogues.

The U.S. befriended a host of corrupt and brutal African dictators like Mobuto Sese Seko and Daniel Arap Moi in exchange for their votes at the UN, their recognition of Taiwan, and their refusal to grant Russia, Cuba and East Germany military basing facilities in their countries.

As a part of its anti-communist strategy, Washington continued to support white minority rule in southern Africa. Washington joined South Africa’s white apartheid government in labeling the ANC as a terrorist organization and Nelson Mandela as a dangerous terrorist. It also refused to support the independence of Angola and Mozambique, largely to protect US access to naval facilities in Lisbon and the Lajes airbase in the Azores. Legitimate independence movements from those two countries were branded as communist leaning organizations and were shunned.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was a major turning point in U.S. policy in Africa under both Republican and Democratic Administrations. With the Soviet political and economic system totally discredited, Africa ceased to be a battleground in Washington’s competition with Moscow. Politically, the U.S. began to advocate for multiparty rule, stronger democratic institutions and greater respect for human rights.

Economically, the United States stepped up its call for African countries to implement meaningful market based reforms and launched a series of development initiatives designed to spur greater economic and trade relations.

African nations responded to the global changes and initiated their own democratic and economic reforms. Across the continent, governments adopted multiparty constitutions, established term limits for presidents and held regular elections. The economic reforms were equally impressive.

Encouraged by the changes, and recognizing the continent’s growing importance, successive Democratic and Republican Administrations embraced Africa.

After two early policy setbacks in Somalia and Rwanda, the Clinton Administration set the tone for Washington’s post-Cold-War engagement in by the next three Democratic and Republican Administrations.

The Clinton Administration increased foreign assistance, welcomed Nelson Mandela to Washington and convinced military strongman Flight Lt. Jerry Rawlings to fully embrace multiparty democracy and presidential term limits in Ghana. In probably his most consequential policy toward the continent, Clinton signed into law the African Growth and Opportunity Act – a land mark trade deal which opened the American market to duty free trade for virtually every African country.

The Bush Administration established PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan to stop the spread of HIV/AIDs as well as the Millennium Challenge Corporation to provide major infrastructure grants to developing countries. And the Obama Administration went even further, launching:

- Power Africa to speed up electrification across Africa;

- Feed the Future to help generate a green agricultural revolution across the continent;

- Trade Africa to significantly expand trade with the five states of the East African community;

- and YALI – the Young African Leaders Initiative to bring hundreds of young, talented and creative African professionals to the United States to bolster their entrepreneurial, management and technical skills.

Washington also collaborated with African countries to deal with a host of transnational issues, including terrorism in Somalia and the Sahel.

Following the catastrophic terrorist bombings on the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998, and the 9/11 attacks, the United States – under both Democratic and Republic Administrations – stepped up its military engagement in Africa and made security cooperation an increasing aspect of its policies.

The Bush Administration opened a military facility in Djibouti on the East African coast in 2001 and six years later, in 2007, established AfriCom -- a unified military command responsible for U.S. engagement across the continent. Military and security engagement in Africa continued under the Obama Administration as it sought to eliminate the al Qaeda East Africa cell in Somalia and to train African militaries to deal with emerging threats in other parts of the continent.

And following the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, the Obama Administration responded by dispatching medical experts from CDC and military units from Italy to build temporary health facilities in Liberia. As the crisis wound down, the Obama Administration helped Africa set up its own Africa Center for Disease control in Addis Ababa.

In 2016, after eight years in office, President Obama had elevated Africa as a priority and had undertaken a score of new high profile public initiatives involving Africa, including hosting the first ever U.S – Africa summit with 50 African heads of state. When Obama walked out of the White House on January 20, 2017, Africa’s standing in Washington had never been higher, and there was a feeling that relations were moving in the right direction.

That changed abruptly after noon on January 20, 2017.

The last four years under the Trump Administration marked a low point in U.S. relations with Africa – reversing the steady improvement which followed the end of the Cold War.

President Trump’s policies uprooted and unraveled U.S. foreign policy around the globe and his policies and vulgar comments about Africa were laced with contempt, personal disdain and racism.

While the Trump Administration left in place most of the major Africa development and trade programs of its predecessors, many of Trump’s “America First” polices demonstrated a strong anti-African and anti-Muslim bias. This is particularly true of the Trump Administration’s aggressive anti-immigration policies. Trump’s visa ban on seven predominantly Muslim countries included five African countries -- Sudan, Somalia, Chad and Libya -- giving the appearance that the ban was not only anti-Muslim but anti-Africa. The Administration’s visa policies also seemed to target Nigeria as it later imposed major immigration restrictions that excluded all but short term business travelers from that country.

The Trump Administration’s hostility toward multilateral organizations also had a negative impact on Africa. The decision to pull out of the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement eliminated America’s $2 billion contribution to the Green Climate Fund. A significant portion of that money would have gone to Africa to help build resiliency against climate shocks.

The Trump Administration also backed away from democracy promotion in Africa, which had taken on greater importance following the end of the Cold War. Funding for democracy programs administered by the State Department and USAID came under serious attack from the White House and the Administration toned down its diplomatic demarches and public statements on democratic backsliding, fraudulent elections and political crackdowns on civil society and the media. The Administration’s disregard for democratic norms at home and abroad probably emboldened a number of authoritarian African leaders to abuse their authority, undermine their constitutions and entrench themselves in power.

One of the most disturbing aspects of Trump’s foreign policy was the re-introduction of great power competition in Africa. In a major speech in December 2018, former National Security Advisor John Bolton -- using language reminiscent of the Cold War -- asserted that the greatest threat to Africa’s progress and success was “not poverty or Islamic extremism, but an expansionist China”. He accused China of using its economic and commercial policies and the country’s “Belt and Road Initiative” to “gain competitive advantage over the United States” and to “hold states in Africa captive to Beijing’s wishes.” The Trump Administration’s effort to put Africa into the middle of Washington’s complex relations with China was a major mistake and a dangerous re-run of a bad policy from the past.

For American to succeed in Africa, the U.S. must show up and most importantly recognize the intrinsic importance of the continent and its people. Africa is not interested in being caught in the middle of a new cold war between Washington and Beijing. And to insert Africa into American’s complex relations with China does little to advance U.S. interests across the continent and throws the U.S. into an unhelpful – and probably unwinnable – debate and competition about which super power is doing the most for Africa.

President Biden’s victory on November 3rd is good news for Africa.

Africa will find Biden to be an enthusiastic partner looking for opportunities to work with leaders to revitalize and rebuild the current frayed relationships.

The first step in this process has started. The Biden Administration has already rolled back and reversed some of Trump’s most egregious policies toward Africa. And he has already started to restore America’s standing across the continent by reaching out to the AU leadership and to several other senior African leaders on the continent.

The President has backed up its first steps by nominating an experienced group of senior foreign policy experts, all of whom have traveled across Africa. His nominee for U.S. ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas Greenfield, is one of Washington’s top Africa experts, having previously run the State Department’s Africa Bureau and served earlier as the U.S. ambassador in Liberia. She is well known and well liked in African capitals. Although she will be based in New York, I suspect she will use her position at the UN and her seat in the Biden cabinet to be a strong advocate for African engagement with Africa.

The Biden Administration will build on a score of bi-partisan policies championed by Presidents Obama, Bush and Clinton, including PEPFAR, Power Africa, MCC and Feed the Future. And the Biden Administration will also utilize the new International Development Finance Corporation to bolster U.S. investment and commercial ties with Africa.

But this is an inflection point in U.S.-Africa relations when doing more of the same may not be enough and where thoughtful, engaged and creative policy making may result in significant, new progress in U.S.-Africa relations.

The Biden Administration has an opportunity to “build back better” in Africa and to construct a stronger and more strategic relationship with the continent and its youthful population, its entrepreneurial business class and its progressive and forward looking leaders.

To do so, it must elevate Africa as a priority. It must take Africa and its most important countries more seriously. It must avoid falling into a Cold War paradigm of making Africa a point of aggressive political competition with China. And it should not make counter terrorism the centerpiece of its policies.

This is the moment to recognize Africa's intrinsic importance:

- its growing importance in international organizations and the international community;

- its expanding economic market and trading potential;

- its youthful population and rising middle class; and

- its entrepreneurial and enterprising spirit.

It must also recognize not only what Africa is today, but also what it can be in the future.

In order to do that, the Biden Administration has to pursue policies that help entrench the U.S. partnership for the next several decades and beyond. It has to be bold.

- In the international arena, the Administration should highlight Africa’s increasing global importance by openly encouraging reform and the expansion of the UNSC to include two new permanent African members with non-veto powers. This would recognize Africa's global importance and make sure Africa's voice is given greater significance and weight in the highest organ of the UN.

- The Biden Administration should advocate for the immediate expansion of the G-20 to the G-22 and to permanently include Nigeria and South Africa, the two largest economies in Africa.

- To expand bilateral partnership with the continent, the White House should host a major summit with African leaders similar to President Obama’s 2014 event and lay the legislative groundwork to do so every two years.

- The U.S. should expand its diplomatic representation around the continent, starting in two of Africa's largest and most important states. It should establish new consulates in northern Nigeria, in either Kaduna or Kano, and in the eastern Congo in Goma or Bukavu. Establishing a consulate in Mombasa, Kenya, should also be given major consideration.

- The U.S. should place a priority on strengthening and expanding its relations with Nigeria and South Africa, by reinvigorating the annual bi-lateral strategic dialogues with both countries.

- As a part of its efforts to expand its relations with Nigeria and South Africa, the U.S. should establish (and provide initial foundational funding for) a U.S.-Nigeria Foundation and a U.S.-South Africa Foundation. The foundations should be public-private partnerships with independent boards, focused predominately on programs for youth and women, computer skills, technology, and STEM education.

- The Administration should work with the Congress to double the equity capital available to the International Development Finance Corp, and allocate a significant tranche of that funding specifically for Africa to promote greater American investments in Africa.

- In the economic arena, with the African Growth and Opportunity Act set to expire in 2025, the Administration should turn its attention to developing a new, comprehensive trade agreement with Africa – one that takes into account the progress Africa has made with its own Continental Free Trade Agreement.

- As a part of the Administration’s expanded economic and business outreach to Africa, it should expand the number of commercial officers around the continent, elevate the Commerce Department’s office dealing with Africa, and appoint a senior officer with Africa and economic trade promotion experience to run it.

- Africa is urbanizing faster than any other continent in the world and the U.S. should establish a major new program that builds direct linkages between major city governments in Africa and major cities in the U.S. The White House should mandate the Department of Housing and Urban Affairs to launch a biannual conference with the mayors of Africa’s fifty largest cities.

- The Administration should develop a special climate change initiative for Africa. Africa will be impacted by climate change more than any other continent in the world, and the Administration’s climate czar, former Secretary of State John Kerry, should make this one of his initiatives.

- Given the erosion of democracy across Africa and the closing of political space for civil society groups, the Administration should establish a new program to increase support for civil society organizations in Africa. Additional funds should be made available to support the strengthening of African legislatures, judiciaries and independent election institutions and election observation groups.

- The Administration should partner with America’s leading tech companies to establish “U.S.A. Tech Centers” in every major African capital and let them be the 21st century equivalent of the former, and much beloved U.S. Information Service libraries that were once a fixture in every major African city.

- The Administration should double the size of the Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI) and move to put this initiative into law under the legislation covering the Fulbright-Hayes program and other major U.S. funded international exchange programs.

The Biden Administration appears to be committed to engaging with Africa, and I remain confident that it will unveil a new set of Africa specific initiatives that will build on the best policies of the past and will reflect a forward looking and progressive view of Africa’s growing international role and bilateral importance to the United States. -- Ambassador Johnnie Carson

Acknowledgements:

Howard on Africa in Brief is published by the Center for African Studies at Howard University. Contributors include prominent scholars, policy makers, Howard faculty, alumni and graduate students. Our papers provide open access to research and make a global contribution to understanding Africa-related issues. The views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s).