Global Conversation Series: The Role of Religion in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism

Howard on Africa In-Brief

A publication of the Center for African Studies, Howard University

Global Conversation Series: The Role of Religion in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism

By Daniel E. Agbiboa, Ph.D.

March 2021

Far from sinking into atrophy with the rise of modernization, as foretold by the “secularization thesis,” the deepening influence of religion has remained visible in the modern world, as corroborated by epochal events such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the Islamic revolution in Iran, the rise of liberation theology in Latin America, and the fall of Communism. The continued salience of religious political parties and militant religious groups across the world, including the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Hamas in Palestine, Jama’at-i-Islami in Pakistan and Bangladesh, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, Boko Haram in West and Central Africa, and Al-Shabab in Somalia, demonstrates that religion is a product of modernity as well as a response to it. All this renews the question raised by Scott Appleby: “Why does religion seem to need violence, and violence religion?” Or, as Mark Jurgensmeyer asks: “Why has violence and religion re-emerged so dramatically at this moment in history and why have they so frequently been found in combination?”

In Africa, as in many regions of the world, proactive actions to thwart efforts by violent extremists to recruit, radicalize and mobilize followers have brought to light the urgent need for a better understanding of how policymakers can effectively engage religious ideas, actors, and institutions in preventing/countering violent extremism (P/CVE) and making durable peace. This is particularly important since, as Jeffrey Seul observes, religion “serves the identity impulse more powerfully and comprehensively in a way that no other repositories of cultural meaning does.”

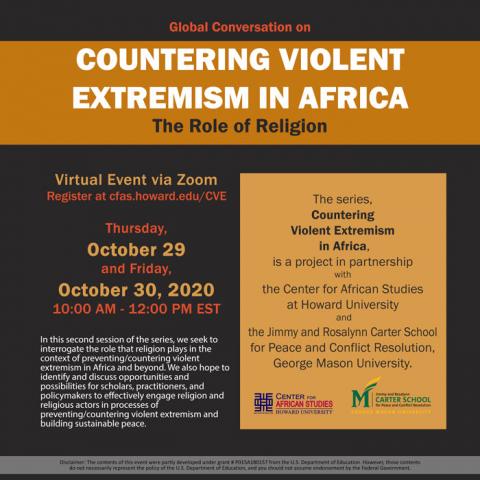

In this second of our Global Conversation Series (GCS), a partnership between Howard University’s Center for African Studies and George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, we seek to interrogate the complex role that religion and religious actors play in the context of P/CVE in Africa. We interrogate Africa in the world, recognizing that the issues of PCVE have no physical borders or disciplinary boundaries. Along the way, we hope to identify and discuss opportunities and possibilities for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers to effectively engage religion and religious actors in processes of P/CVE and building sustainable peace.

The GCS was divided into two days. On day 1, we sought to understand the concept and drivers of violent extremism. On day 2, we turned our attention to what works and what does not work when it comes to P/CVE. Below, I provide a summary of the event.

Day 1: Understanding Violent Extremism: Concept Analysis and Drivers

Over the last few years, preventing and countering violent extremism has featured prominently as an organizing logic and central priority on the agenda of researchers and policy makers at national and international government agencies. Yet, the concept of violent extremism, and its application to concrete local settings and communities, remains contested, even problematic. How should we understand and apply the concept of violent extremism? What is the relationship between “extremist” ideas and terrorist violence? What are the key drivers of violent extremism? Why is religion so commonly associated with (violent) extremism? These are some of the questions we sought to tackle on the first day.

To help us unpack these pertinent questions, we fielded four expert panelists: Muhammad Fraser-Rahim, the Executive Director of North America for Quilliam International and an expert on violent extremism issues in Africa; Abdulbasit Kassim, a PhD candidate at the Department of Religion, Rice University, and a Visiting Doctoral Fellow at the Institute for the Study of Islamic thought in Africa at Northwestern University; Audra Grant, a Senior Research Manager at NORC, University of Chicago; and Darren Kew, Associate Professor in the Department of Conflict Resolution, Human Security and Global Governance at the University of Massachusetts Boston. These diverse speakers reflect and reinforce the complexity of P/CVE in postcolonial Africa and the contemporary world.

Fraser-Rahim started us off with the critical observation that much attention has been devoted to preventing individuals from participating in violent extremism, understood as violence undertaken by non-state actors that is inspired or justified by, and/or associated with, an extreme political, religious, or social ideology. However, less attention has been paid to the processes of disengagement and deradicalization. Yet, as he argues, processes of disengagement, deradicalization, rehabilitation, and reintegration are crucial to any holistic P/CVE strategy. He identifies three typologies of violent extremists in Africa, to wit: non-religiously based extremists (e.g. Lord Resistance Army); Islamist extremists (e.g. Boko Haram, Al-Shabab); and foreign terrorist fighters, which denotes radicalized individuals who travel or intend to travel beyond their homeland. Fraser-Rahim concluded by stressing the need to weave local/community resilience initiatives into P/CVE approaches, while also acknowledging that the state matters to any successful implementation of P/CVE frameworks.

Audra Grant underscored the severe limitations of security-centric approaches to PCVE in Africa and globally. Relying exclusively on military might, she argues, do very little to engage the local drivers that create a fertile ground for the breeding of violent extremism and push people to embrace radical ideologies. These drivers include ideologies, grievances associated with lack of economic opportunities or un(der)employment, community disintegration, and other micro-level dynamics. She argues that strategies that pay attention to the social dynamics of violent extremism are likely to be more effective. For P/CVE approaches to be effective, argues Grant, local communities and their plight must be foregrounded. Grant called attention to the fact that women are disproportionately targeted by violent actors (e.g. through rape). However, women are not simply victims but also perpetrators of violent extremism and agents of sustainable peacebuilding efforts. In so doing, Grant draws our attention to the complex agency of women in P/CVE processes. She contends that while much ink has been spilled on women’s role as victims or agents of violent extremism, their role as local peacemakers has remained “less explored and not fully harnessed.”

The next two panelists, Abdulbasit Kassim and Darren Kew, took a case-study approach, focusing on legacies and dynamics of Boko Haram and Christian-Muslim relations in West and Central Africa. Boko Haram is a Salafi-Jihadi group that originated in northeast Nigeria but has since extended its reach to Cameroon, Niger and Chad—riparian countries that form the Lake Chad Basin region. Since 2009, the Islamist group has killed thousands and displaced millions in what the United Nations calls the worst humanitarian crises on the African continent. Much of Darren Kew’s work has been in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, and focused particularly in Muslim-Christian but also intra-religious dialogue in the predominantly Muslim northern region. Kew began his presentation by noting in passing that there are significant number of Christian fundamentalist groups in Nigeria that have embraced the message and methods of violence, although not at the scale we have come to expect of Islamist groups such as Boko Haram. Too often researchers and practitioners focus on the systemic drivers of violent extremism, including poverty, youth unemployment, state failure and state repression. Kew debunks the popular view among religious groups and leaders that violent extremism has little to do with religion and much to do with relative deprivation and horizontal inequalities, as well as the view that religion offers a façade for poverty, deprivation and state failure. Instead, Kew underscores the centrality of religion and religious beliefs as key motivating factors in violent extremism. For Kew, religious beliefs are critical to overcoming violent extremism and de-escalation strategy in Africa today. To substantiate this salient point, Kew contrasts the militant religious group Boko Haram in northern Nigeria with the socio-economically driven oil militants in the south. Why is it that religion seems to be so connected to violent extremism? In response, Kew identifies four elements that shed light onto why religious beliefs are so conflict-prone. First, violent extremist groups tend to have a utopian vision. Second, the method of achieving this utopian vision is often expansionist (e.g. the Global Jihad). Third, the collectivist nature of religious beliefs, by which he means the cohesiveness of the in-group, the importance of “sticking together” and recognition that one is not just an individual but belong to a larger group. This collectivist perspective “hardens perspectives” from a negotiation vantage point. And Fourthly, the divine mandate that is often ingrained in the violent ideology of extremist groups. Combined, these four elements make it a Herculean task to negotiate with violent extremist groups. Kew argues that the religious beliefs of violent extremist groups make it difficult to de-escalate conflict once it has started. He subsumes all these four elements under an identity dimension, contending that changing the personal identity dimension is extremely difficult from a policy perspective. Kew underscores the need for alternative ideologies and visions as a counternarrative to the utopian vision of violent extremist groups.

And finally, Abdulbassit Kassim gave a stimulating mapping of the ideological contours of Islamist movements in sub-Saharan Africa. Kassim makes the central argument that violent extremist movements did not emerge in a vacuum; context matters, says Kassim, when seeking to understand and counter violent extremist groups. While scholars and practitioners tend to focus on Islamist movements, Kassim argues that violent extremist groups actually cut across different religions, echoing Kew’s earlier point. Kassim adduces the example of Kaduna in northern Nigeria where some violent extremists are closely aligned with the Christian theology. He identifies the various lens through which violent extremist groups are explained today. On the one hand, some scholars focus on religious doctrines, poverty, and political instability in Africa. Others, however, underscore the role of “personal agency” (i.e. why do certain individuals embrace violent extremist ideologies?). Kassim emphasizes the role of religious doctrines and argues that the ideology of violent extremist groups is not radically new. To corroborate this point, he delves into the intellectual history of Islam and the longue durée of dissident Salafist groups such as Boko Haram in northeast Nigeria.

Day 2 Speakers: Countering Violent Extremism: What Works and What Doesn’t?

On day 2 of our GCS, we turned our critical attention to practical questions regarding P/CVE. We asked our expert panelists to grapple with the questions: What works (and what does not) when it comes to P/CVE? How effective are P/CVE programs for reducing terrorism and violent insurgencies? Like day 1, we had a different group of expert panelists to shed light onto these questions, including Marc Gopin, Professor and Director of the Center for World Religions, Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University; Sheherazade Jafari, Director of the Carter School’s Point of View International Retreat and Research Center; Altaf Husain, Assistant Professor at Howard University’s School of Social Work; and Reverend Fr. Bazemo Barthelemy, a policy analyst with the Africa Faith and Justice Network.

The conversations opened with Jafari’s presentation. Jafari began by by acknowledging that among international and national approaches to P/CVE and building sustainable peace, religious actors are increasingly recognized as important partners. Yet, while religious actors feature prominently in P/CVE practices, lay leaders—particularly religious women—are generally shunted to the margins or simply overlooked by policymakers and practitioners. On the other hand, in recent years, important attention has been placed on the gender dimensions of P/CVE and the need to promote women’s participation, particularly through the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. This effort notwithstanding, Jafari notes that religious women as agents of change in PCVE processes are ignored or seen only through the framework of victimization, while the intersections of religion and gender writ large are defined in sedentarist and ultimately misogynistic terms. Such approaches, says Jafari, result in P/CVE initiatives that are, at best, limited in their effectiveness and, at worst, dangerous, including in reinforcing harmful gendered norms and practices that inform the radicalization process. In this, Jafar reinforces Audra Grant’s central argument from day 1.

Drawing on examples from different contexts, primarily in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, Jafari underlines the need for an intersectional gender inclusive approach to P/CVE that acknowledges the dynamic and localized experiences of religion, gender, and power. She argues that such an approach helps to better understand the ways religion and gender are intrinsically interwoven. Jafari’s presentation centered the work of faith-based women who are directly opposing violent and misogynistic interpretations of their religion through new hermeneutics with a gender inclusive lens, challenging both traditionalist or extremist ideologies as well as mainstream, dualistic P/CVE frameworks that rely on harmful masculine/aggressive vs. feminine/passive or religious/irrational vs. secular/rational binaries and stereotypes. Jafari admits that while a focus on transforming harmful masculinities is still rare among PCVE processes, religious actors—as trusted community leaders—hold enormous potential to help redefine and reconfigure gender norms and promote healthy masculinities in efforts to build inclusive, sustainably peaceful communities.

Next in line was Altaf Husain who gave a affective and embodied presentation on how inherent anti-religion and anti-youth bias constitutes a major limiting factor in P/CVE approaches and explains why most P/CVE approaches fail. Husain begins by noting that the topic of terrorism interests him at the personal and professional level. As a father of Muslim children, Husain has had to contend with the fact that, in the current securitized and constricted paradigm of P/CVE, he and his children are falsely assumed to be at-risk for radicalization and lumped into a “suspect community.” He describes excruciating experiences of been profiled at airports. 9/11 was personal for Hussain because he lost a friend and mentor who went to work in the World Trade Center that morning but never came home. Husain argues for the need to rework existent framework of P/CVE because of its inherent bias which perfunctorily accords the status of “violent extremists in waiting” to Muslims, especially youths. For Husain, there is no justification or hard evidence supporting the premise that “somehow self-identifying Muslims have a greater propensity to become violent extremists.” In Husain’s view, positioning P/CVE strategies within a broader context of community outreach to Muslims is both disingenuous and an utter waste of resources. Instead, Husain underscores the need for P/CVE approaches to pay critical attention to transformative social work perspectives. In social work, argues Husain, “we insist that intervention strategies must meet clients, constituents, and communities where they are.” In particular, disaffected and marginalized youth of all races and religious backgrounds should understand and feel that efforts to engage them are genuine and focused on their wellbeing writ large as opposed to a disproportionate interest in preventing them from becoming (potentially) radicalized.

Fatma Ahmed’s presentation used a case-study and social network analysis in Somalia to unpack for us the drivers of violent extremism. Somalia is a highly volatile environment, within which historical, political and social dynamics have been exploited by violent extremist groups such as Al-Shabab. Based on a social network analysis, Ahmed’s case study points up three central factors in the radicalization process. Firstly, she identified power and identity as pathways to radicalization in Somalia, stemming from familiar issues of state failure manifested in unemployment and insecurity. Ahmed argues that in Somalia, youth unemployment is high and intrinsically intertwined with identity and a sense of self-worth. She argues that Al-Shabab has cashed in on this condition to recruit new members, offering them living wages and material goods which in turn gives youth a sense of status, power and belonging. Insecurity, says Ahmed, leads to an overwhelming sense of powerlessness among Somali youth. In a context where rural communities cannot rely on the central government for public or political goods, Al-Shabab has often stepped in to provide alternative livelihoods. Secondly, Ahmed calls attention to the role of communications, that is, how potential recruits consume and share information. Her study found that across Somalia’s four regions, Garowe, Mogadishu, Baidoa and Kismayo, the vast majority of people have access to smart phones, and radio is widely used. Importantly, there is a high reliance on friends and families to voice concerns and frustrations about government failure, but also to seek advice on pressing matters. Ahmed’s study shows that Al-Shabab often exploits social and mobile networks to recruit and radicalize vulnerable groups. Finally, Ahmed underlines the role of trust. Her study found that the strongest trust relationship exists between friends and family members. Notably, individuals in her study were less likely to seek advice from NGOs and Human Rights CSOs. She used this point to underscore the critical role of trust in P/CVE frameworks since it enables predictability, community and collaboration. P/CVE approaches must take seriously the “highly complex trust networks” that often exist in local communities. She concludes that no P/CVE campaign would succeed without “knowledge on where people receive information, or who is trusted to deliver those messages.”

Next was Marc Gopin, who has worked for more than three decades as a conflict practitioner, including over a decade in Syria. According to Gopin, the clashing, conflict, and power struggles associated with male-dominated systems tend to constrict the ability of men to pursue peace processes in society. As a result, women, particularly those disempowered by hierarchies across the world, tend to have significant leverage when it comes to conflict resolution. This is particularly true, says Gopin, because nobody is paying attention to them or because they are not considered part of or integral to the power structures in traditional religions. Gopin argues powerfully that P/CVE approaches must be rooted in practice rather than in lofty theories with little to no resonance with the daily lives of individuals and communities in conflict-affected regions. Much of CVE frameworks, argues Gopin, are driven not only by “junk science,” reiterating a term used by Altaf Husain, but also by hidden and narrowly-constructed “agendas.” Gopin argues that P/CVE must move away from a dominant approach that automatically links certain religions (e.g. Islam) with violent extremism. Gopin ends by highlighting the need for more emphasis on compassion and solidarity, especially when dealing with the “alienated other.” In short, Gopin calls for more emphasis on the affective dimension of P/CVE approaches.

Finally, Barthelemy Bazemo gave a fascinating presentation on the role of religion and local peacebuilding initiatives in PCVE in sub-Saharan Africa. Barthelemy approached the issue of violent extremism as both “a man of faith” and “a concerned scholar.” This is because his native Burkina Faso has been negatively impacted by violent extremism and state failure. Bazemo’s presentation was inspired by Catholic social teachings that emphasize the need for structures that uphold human dignity. He begins by pointing out that violent extremism has no borders; it is a multifaceted and extremely diverse phenomenon affecting both the so-called developed and developing world, from extreme right-wings hate groups to ethno-religiously motivated violence. Bazemo makes a strong case for a critical approach to framing security challenges in Africa that engages the straddled issues of development, governance, and faith in conversation with culturally-appropriate or endogenous means of peacebuilding. This tripartite approach, says Bazemo, can foster community resilience. Criticizing the “hard power” nature of P/CVE approaches that tends to exclude and alienate rather than include, Bazemo calls for more attention to locally driven conflict resolution initiatives.

In conclusion, all panelists from both days emphasized the need to move beyond simplistic and homogenizing P/CVE approaches, as well as the need to recognize that religion is socially embedded and constantly in touch with the practice of everyday life.

Acknowledgements:

Howard on Africa in Brief is published by the Center for African Studies at Howard University. Contributors include prominent scholars, policy makers, Howard faculty, alumni and graduate students. Our papers provide open access to research and make a global contribution to understanding Africa-related issues. The views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s).