Pluralities of Faith: Experiencing the Distinctive Islam of West Africa

By Sobia Saleem

In this essay, Sobia Saleem, a 2019 participant in CAORC’s faculty development seminar to Senegal, writes about her visit to the Great Mosque of Touba and experiencing West Africa’s distinctive Islamic traditions. All photos are courtesy of the author.

May 24, 2020

As an American Muslim participant in the 2019 faculty development seminar to Senegal, I found Islam in West Africa to be quite different from the religion I grew up with and learned in the U.S. However, seeing and experiencing these differences allowed me to have a broader and more expansive view of my faith; indeed, by seeing how Islam is practiced in Senegal, I was reeducated about my own religion.

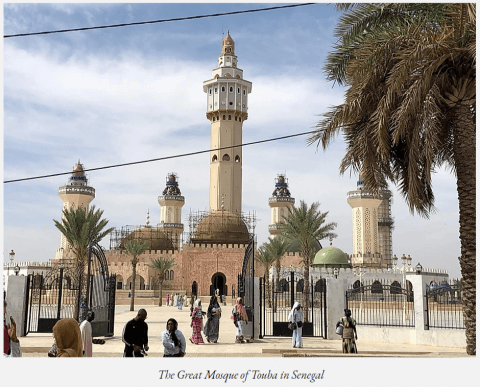

During the seminar, one of the first cities we visited outside Dakar was Touba, where we stopped to see the Great Mosque—and great it was. With shading umbrellas reminiscent of those of the Great Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and its cool white marble that bespoke both purity and the simplicity of life and death, I found myself immediately transported, mind and spirit, to a space of intense holiness, the kind that connects one to something truly sacred. At the time, I felt incredibly connected to Muhammad, his city, and his mosque because of the striking visual and spiritual semblance the Great Mosque of Touba had to Al-Masjid An-Nabawi in Medina. Just like I did when I visited the other great mosques in the Islamic world, I said a small prayer and took pictures of the beautifully intricate domes as I felt a wave of familiarity wash over me.

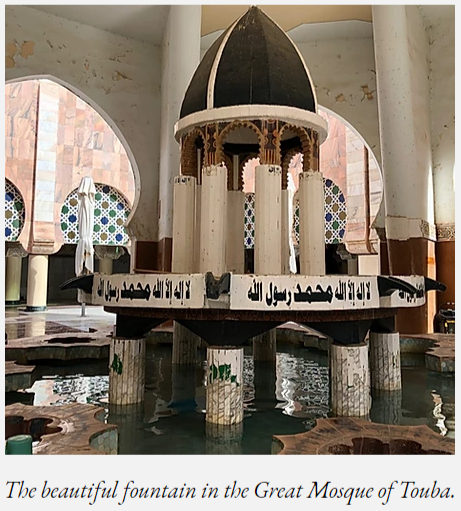

—until I was faced with the realization that Islam in Senegal, while reminiscent of more traditional forms of Islam, is at the same time entirely unique in its Sufi framework. When my colleagues and I walked into the mosque, we quickly realized no one was allowed into the main prayer areas except those who were Muslim, so being Muslim, I proudly made my way into the prayer area, only to be stopped from entering. Apparently, I didn’t look Muslim. I had my headscarf on perfectly, and I even put a wraparound skirt over my sweatpants. I had to speak a little Arabic before I was let in, but it was worth it—before me was a beautiful fountain for wudu, the Islamic version of ablution.

The fountain reminded me of the ones I’d washed my hands and feet in Morocco a few years ago, so I made my way and started washing my hands, only to have an elderly man yell at me to “stop!” I didn’t understand why, but it was clear that he wanted me out. After fervent hand motions on the man’s part, I eventually realized that I had attempted to wash myself in the holy drinking water of ZumZum! Luckily, I had only gotten as far as rinsing my hands and hadn’t gotten to the part of washing my feet! I felt so embarrassed, but the kind man led me to the ablution area, where again, although I thought I was covered modestly enough for even my mother not to complain, I was repeatedly asked if I was Muslim. Never had I felt so unmoored.

After visiting the mosque, I entered the adjacent library, which was filled with beautiful copies of the Quran. What I found most interesting in the library was the introduction to Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba, a major Sufi saint in Senegal. The Islam I had been raised with preached that the very idea of saints was haram or “forbidden,” but here in Senegal, the better part of a country, including some of its secular artists, valued this man’s holiness. Much like Muhammad, the Sheikh’s face was a mystery, but objects and texts associated with him were sanctified by his spirit, bringing calm, patience, and a wholeness to those who interacted with him.

For me, Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba allows the inaccessible parts of the Prophet Muhammad to become accessible. The figure of the Sheikh connects with people in very real, human ways through his depictions and popular re-imaginings, a connection that, precisely because of his often (and ironically) deified position, tends not to be associated with Prophet Muhammad.

Moreover, Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba allows for a decentering (or even re-centering) of the locus of power in the Islamic world. Sufi Islam, while often pushed to the fringes of orthodox Islamic theology, is widely practiced by a majority of Muslims in Senegal. Similarly, Africa’s deep Islamic traditions that often go unrecognized in standard historical renderings of the spread of a distinctly “Arabized” Islam across the medieval world are foregrounded here.

In the mosque’s library, one of the pictures that captured my attention was that of a towering, life-sized figure of the Sheikh; even his image had an aura that could not be ignored, that demanded respect and introspection from its audience. I cannot pretend that I did not feel Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba’s presence that day in his image, in his Qurans, and in his library. His spirit touched me, and the reality of my Islam was forever changed.

CAORC’s 2019 faculty development seminar to Senegal was organized with the West African Research Center in Dakar, Senegal, and supported by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and the following U.S. National Resource Centers in African Studies: Boston University, Howard University, Indiana University, Michigan State University, University of California, Berkeley, University of Kansas, and University of Wisconsin, Madison.

About the Author

Sobia Saleem teaches in the Department of English at Ohlone College in Newark, California. She was among the 17 faculty participants in the seminar “Diversity, Religion, and Migration in West Africa,” an intensive capacity-building and curriculum development seminar held in Senegal from January 6–23, 2019.

Learn more about CAORC Faculty Development Seminars.